The Racoviţă family is an old family from Moldova, Romania, with origins documented from the XVI century. The family tree includes a number of high ranking figures, including principate rulers such as Mihai Racoviţă, who distinguished themselves as both nation builders and brave warriors. Emil’s father, Gheorghe Racoviţă, nicknamed Gheorghieş was a judge, and, as a founder of the “Junimea” society, played an important role in the cultural and intellectual life in Iaşi, the capital of the Moldova Principate. His mother, Eufrosina, nee Stamatopol, dedicated herself to raising of the only surviving child, Emil, from the three that the couple had. The other two had fallen prematurely to illness.

Emil grew up in a warm and loving environment in the Şorăneşti mansion, a small village in the county of Vaslui, where the family owned land. In elementary school, he was a pupil of Ion Creangă, from whom he learned the gift of speaking using the soft moldavian language with unconventional terms and accent, style he used even in formal speeches at the Romanian Academy. He continued his schooling in Iaşi, first at the National Liceum and then in private at the “Institutele Unite”, where he had as colleagues other Romanian personalities: Sava Atanasiu, Grigore Antipa, Dimitrie Voinov şi Nicolae Leon. His teachers there were the historian Alexandru D. Xenopol, the chemist Petre Poni şi geologist Grigore Cobălcescu. The latter inseminated the young Racoviţă with the passion for nature and thus played a crucial role in his future career choices.

Encouraged by his father to follow a legal career, Racoviţă left for Paris in 1886 and registered to study Law. However, his passion for natural sciences, made him attend the classes and presentations held by Dr. Léonce Manouvrier at the Superior School of Antropology. Soon after he received his license to practice law, Emil registered for the Faculty of Sciences at Sorbonne University, where he worked with to renowned zoologists: Prof. Henri de Lacaze-Duthiers and Asst. Prof. Georges Pruvot.

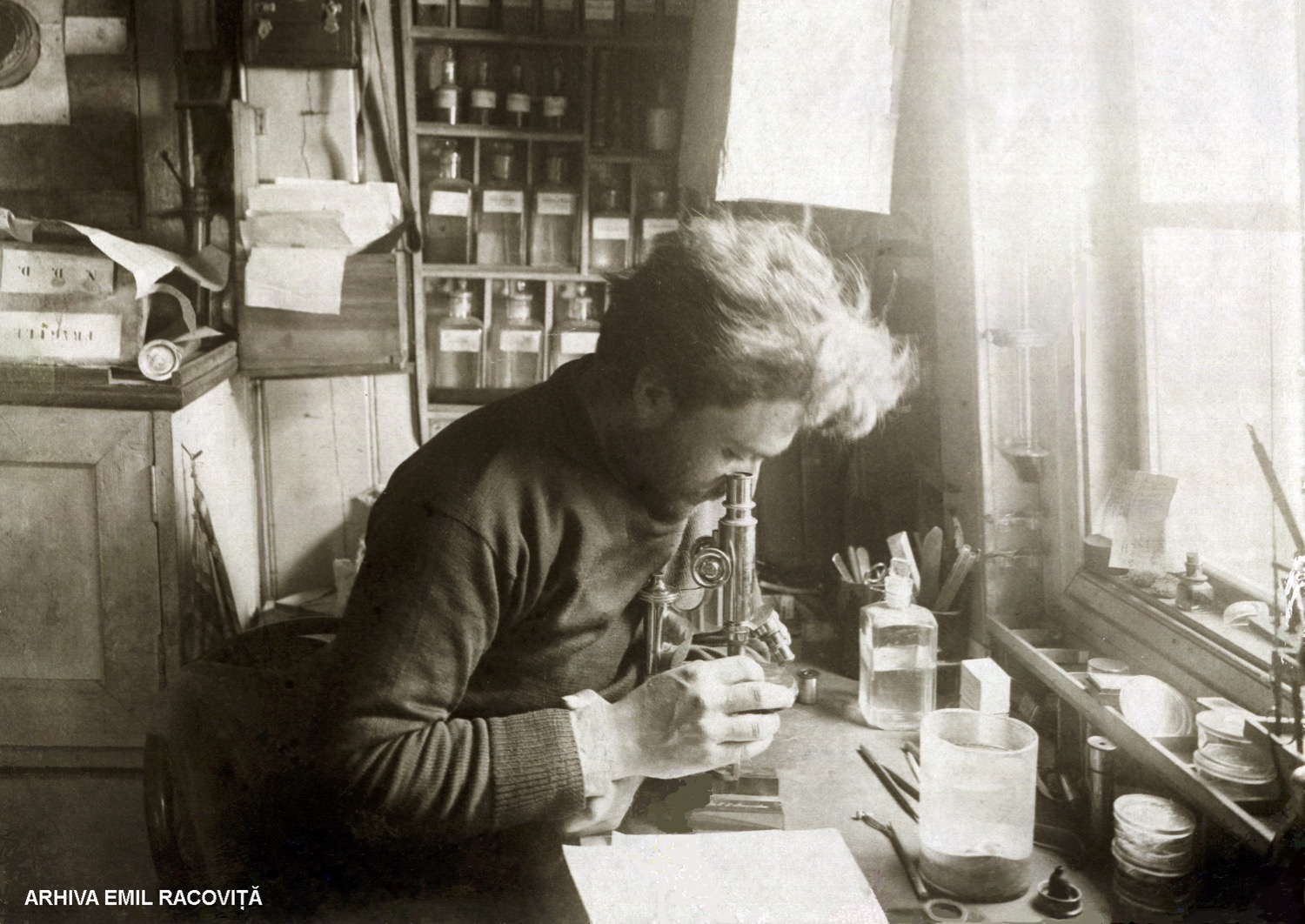

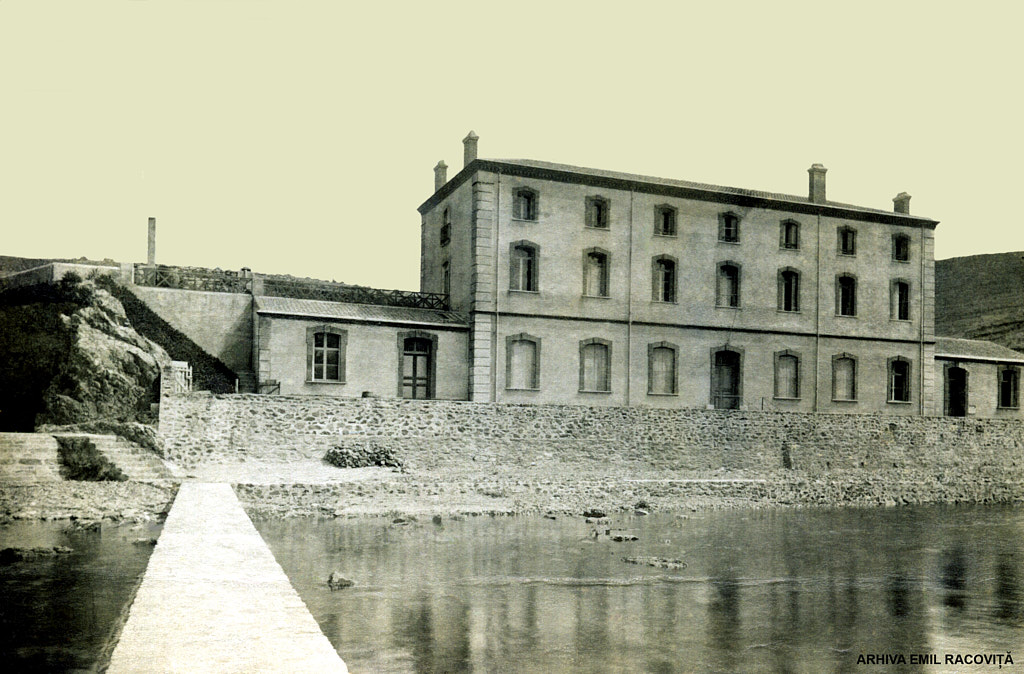

After his graduation in 1891, he remained in France to work on his doctoral dissertation at the “Arago” Oceanographic Laboratory at Banyuls-sur-Mer, under the supervision of the same Lacaze-Duthiers. After five years of intense research, Racoviţă received his doctoral degree based on the public defense of his dissertation on the cephalic lobe of polychaete worms – the most common marine worms. This was his first step toward an illustrious career.

About this time, military duty called Racoviţă back to Iaşi; this might have signaled the end of his stay in France. However, less than a month later he received a letter from Liège containing an invitation to join an Antarctic expedition.

The invitation was too compelling for Racoviţă to refuse and he wholeheartedly agreed to join as the biologist of the daring expedition organized and led by the Navy Lieutenant Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery, aboard the ship “Belgica” between 1897 to 1899. Thus Belgica became the first Antarctic expedition whose goal was a program of complex scientific observations and research beside exploring unknown territories. It also became the first expedition to spend an entire polar winter locked in the Antarctic ice shelf, and survive it relatively unscathed.

To accomplish this ambitious program, 19 men embarked on a ship measuring only 32 m (95 ft) by 6.5 m (20 ft) and trusted this tiny shell to carry them through. The risks were enormous, and two of them paid with their lives. Considering the challenges of the task they set for themselves, the expedition was a resounding success, a success to which the young Romanian biologist contributed significantly. Among the other participants, were the First Officer, the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who later went on to be the first to reach the South Pole, and who declared later that Racoviţă was “a precious companion and an explorer who continuously encouraged everyone”. Racoviţă was the main driver behind the unusually rich collection of scientific materia gathered throughout the expedition – he brought back 1200 zoological and 400 botanical samples. Adding to this there were numerous detailed observations, in particular whales, seals, and Antarctic birds.

The study of all the material required the attention of no less than 74 experts, while Racoviţă reserved four areas for himself. Unfortunately, his additional duties in the following years prevented him to elaborate all but the one dedicated to whales. To date, we know that in the “Grigore Antipa” Natural History Museum in Bucharest, there exists a 513 page manuscript, only partially finalized which was intended to constitute the study of seals. Given the success of the work on whales, which served as the main reference for the science community for a long time, it is unfortunate that his work on seals was not widely published.

On return from the expedition, looking for a place to optimally study the valuable collection, Racoviţă chose the Arago Laboratory, where Prof. Lacaze-Duthiers not only welcomed him, but started

envisioning him as his successor. To this effect, on Nov 1, 1900, Emil Racoviţă was named vice-director of the laboratory, while Georges Pruvot was the director. A year later, these two collaborators were named co-directors for the „Archives de Zoologie expérimentale et générale”, one of the most prestigious scientific journals in Europe founded in 1872 by Lacaze-Duthiers. These functions clearly illustrate the stature achieved by Racoviţă in the French scientific community not long after reaching the age of 30. These new responsibilities kept him extremely busy, and it is more surprising to learn that in a country considered a European cultural and scientific center, resources dedicated to research were slim – to an extent that Racoviţă needed to support the laboratory and the journal’s publication using his own money, drawn from his ancestral estate at Şorăneşti. To his credit, these and future challenges only strengthen his resolve.

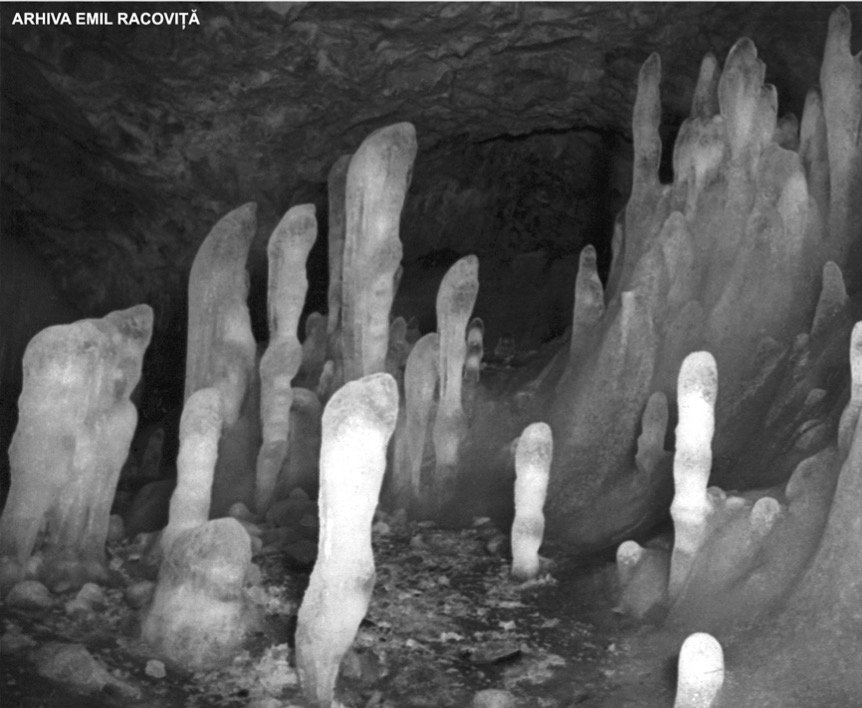

During one of the regular research lab trips undertaken in the summer of 1904 in the Western Mediteranean basin, Racoviţă visited a renowned cave, Cuevas del Drach on Mallorca Island. Here, in the dark waters of one of the great lakes inside the cave, he collected a little crustacean, yet unknown to science. He named it Typhlocirolana moraguesi, and it became the cornerstone fo his career as a biologist. This little animal, transparent and blind (missing the eyes completely) was a clear example of adaptation to the dark environment in caves. Racoviţă realized that the study of life in caves can drive the understanding of evolution – and thus, he dedicated his career to this area abandoning the oceanographic research.

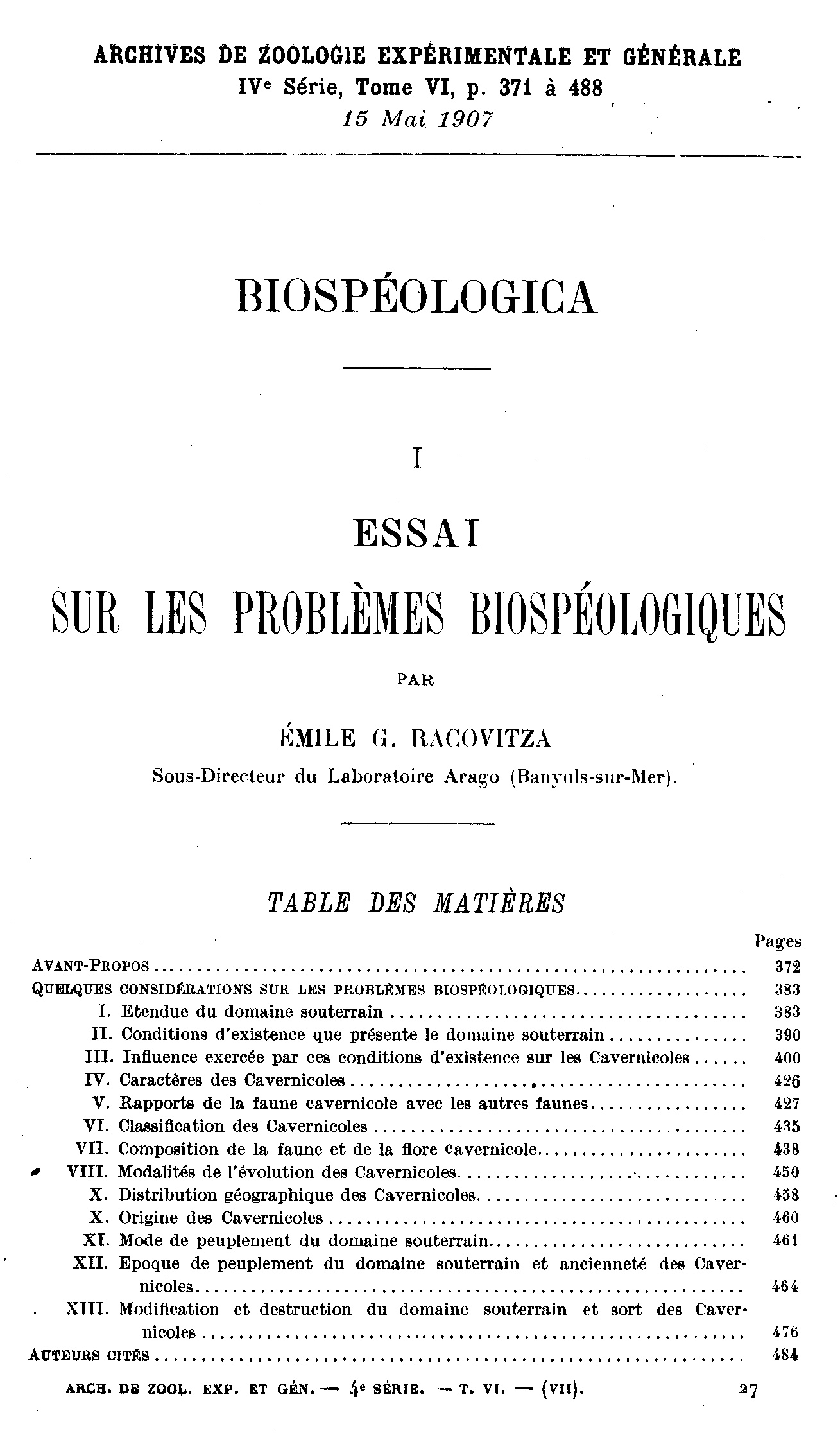

To follow on this discovery, he started by looking at the exiting published work and realized the various opinions of different zoologists were so divergent that there was no coherent view for the study of fauna in caves. Therefore, he needed to create his own means to understand the nature in the subterran world, which implied exploring as many caves as possible, in diverse regions of the world. For this, he needed help, and he was able to find René Jeannel, a young and resourceful medical doctor with an additional degree in natural sciences. Starting in the summer of 1905, they intitated the exploration of the caves on both sides of the Pyrenees Mountains. They were so proficient, that Racoviţă was able to create a coherent view and publish it as the famous “Essai sur les problèmes biospéologiques” (Essay on the biospeleological problems), published in 1907. Thirty years later, Jeannel maintained that the essay “was good from the beginning and it is still the established standard of biospeleology”.

In spite of the importance of the “essay” for the future of biospeleology, for Racoviţă it was only the seed of his vision. Similar to the Antarctic expedition, the study of the material collected during his speleological expeditions required experts in specialized areas and they needed to coordinate toward a common goal: the understanding of the natural history of the subterran world. To this end, Racoviţă created “Biospeleologica”, a new scientific forum that he led with Jeannel as his second in command. They gathered 40 collaborators, some of which were ready to explore caves, and together they uncovered numerous mysteries found in the abyss of the caves. By 1919, this group of people had achieved an unexpected set of results: the exploration of close to 800 caves in the main karstic regions of Europe and North Africa, collecting 20,000 subterranean animals, and publishing 41 scientific works totalling 3,400 pages under the aegis of “Biospeleologica”. Looking back, these results are even more astonishing, considering that during the first World War, Racoviţă suspended all research activities and focused on leading/managing the military hospital that was located temporarily in the Arago Laboratory.

The summer of 1919 brought a new turning point in Emil Racoviţă’s life. After the peace was established and the Treaty of Trianon brought Transylvania back to Romania, Racoviţă received a letter soliciting his help in organizing what became the first Romanian university in Transylvania. His birth country was calling on him to serve with his international recognition and prestige and Racoviţă accepted with the condition that the new university create for him a new institute for scientific research in speleology. Consequently, the law establishing the Speleological Institute in Cluj was passed on April 26 1920, the first research institute of its kind in the world, with Emil Racoviţă at its helm.

Racoviţă’s vision for the institute was to provide an official framework for the “Biospeleologica” forum, and therefore, making Cluj (the spiritual capital of Transylvania) the global epicenter of biospeleology. He continued to lead the endeavor, and convinced René Jeannel to come to Cluj as vice-director of the Speleological Institute and Biology professor at the Faculty of Sciences. In 1922, they were joined by the Swiss zoologist Pierre Alfred Chappuis, as assistant director. The rest of the scientific personnel included the assistants Valeriu Puşcariu, Radu Codreanu and Letiţia Chevereşanu.

Eager to explore the caves of Apuseni Mountains in Western Romania, Racoviţă started his biospeleological campaigns in the summer of 1921. However, a small heart attack two years later forced him to give up field work.

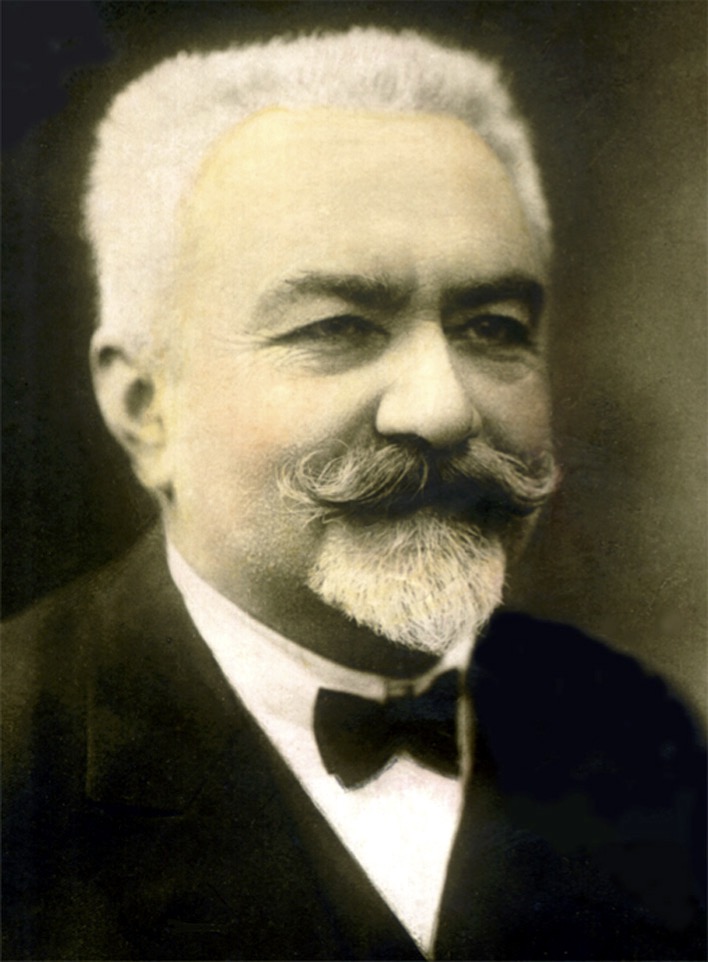

What followed was a long and demanding set of leadership administrative functions that left him with very little time for research. After being a corresponding member of the Romanian Academy since 1905, he became full member in 1920 and President of the Romanian Academy in 1925, serving as President for three terms (1926-1929). Between 1922 and 1926 he served as Senator for the Cluj University. He took the University leadership as rector in 1930 and vice-rector in 1931. In 1920 he became founder of the Sciences Society of Cluj, presiding from the beginning until his death. In 1920 he also became a member of the General Association of University Professors, and operated as President of the Cluj section. In 1922 he founded the Cultural Association for the dissemination of French culture and language, better known as “Circle Ronsard”. He was a founder and President (1921-1933) of the first Romanian touristic society in Transylvania, “Frația Munteana” (the Mountains Brotherhood). In 1928 he became President of the First Congress of Romanian Naturalists (Cluj, April 18-21) and he used this position to drive the legal framework for nature conservation in Romania. In 1932, while Jeannel going back to France to organize the vuvarium at Jardin des Plantes and the Entomology Chair at the Natural History Museum in Paris, Racoviţă assumed the duties of teaching the general biology class at Cluj University.

Emil Racoviţă’s body of work arguably establishes him as one of the most prominent Romanian biologists, despite the heavy burden of all administrative roles. The list of his accomplishments includes: the first scientific study of the Antarctic flora and fauna in the world; the founder of biospeleology as a standalone science area; the thought leadership and establishing research principles stating that to fully understand a natural species, one has to holistically study its entire history, not just its systemic position and area of habitat. Moreover, he is the sole Romanian biologist to have elaborated an original theory of natural evolution. His theory emphasized the role of isolation in the evolution of new species, and in 1912 he formulated a simple and effective new definition of species: an isolated colony of blood relatives. He was also one of the first scientists to raise the alarm on the perils of climate change, pointing to the artificial environments that enabled human population growth at exponential scale world-wide, thus raising the dangers of influencing climate at large uncontrollable levels.

Emil Racoviţă’s status as an internationally recognized leader in his domain is reflected in the numerous international functions held: full member of the French Zoological Society (1893) and its Honorary President (1925), member of the Romanian Geographical Society (1900), Honorary member of the Romanian Naturalists Society (1900), member of the French Geographical Society (1900), member of the French Entomological Society (1906), Corresponding member of the London Zoological Society (1910), President of the Paris Speleological Society (1910), Corresponding member of the Barcelona Natural Sciences Society (1922), member of the Paris National Institute of Anthropology (1922), Honorary Doctor of the Lyon University (1923), member of the Romanian Ethnographic Society (1923), member of the Paris Biological Society (1925), member of the Romanian Geological Society (1930) and its President (1934), Corresponding member of the Spanish Natural History Society in Madrid (1930), Founding member of the Biogeographical Society in Paris (1935), Corresponding member of the Medical Academy in Paris (1944), member of the London Zoological Society (1947).

The devotion that Racoviţă put into promoting culture and science was also recognized by State officials world-wide: he was named Knight of the Order of Leopold II of Belgium (1899), as well as Knight (1922) and then Commander (1927) of the French Legion of Honor. In Romania, he was granted a large number of medals, including: Order of the Star of Romania – Officer in 1899 and 1922, Grand Officer in 1928 and the Grand Cross in 1942, Bene Meriti (First Class in 1900), the Order of the Crown of Romania (Grand Cross in 1930), Order for For Merit (Commander in 1931), The Cultural Merit for Theoretical and Practical Science (Knight in 1931, Officer in 1934, and Commander in 1943), Service Honors for 25 years of service (1932), and Order of Faithful Service (Grand Officer in 1939).

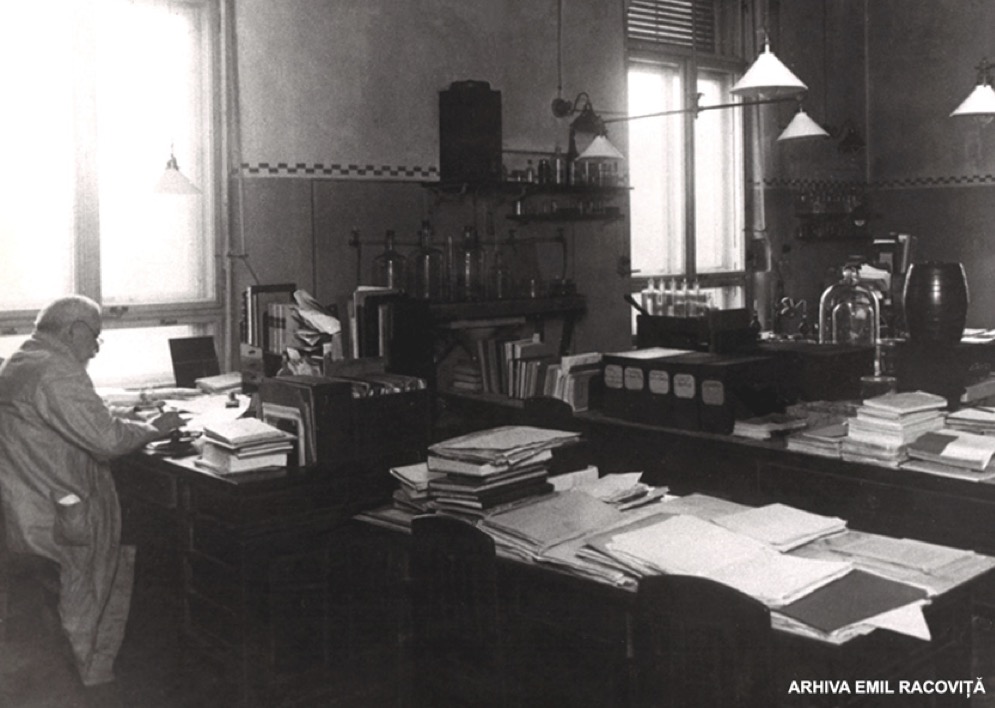

His last years were the most difficult. In September 1940, the Vienna Diktat forced Romania to cede the northern part of Transylvania (including Cluj) to Hungary. Most of the Cluj University relocated to Sibiu, except for the Science Department which relocated to Timişoara. Relocating with the Department, Emil Racoviţă left the Cluj Speleological Institute under the direction of Pierre Alfred Chappuis (as a Swiss, he was a citizen of a neutral country). During the war, the 70 year old professor used his energy to keep the Science Department active. Coming back to Cluj, he attempted to do the same with the Speleological Institute, however, it was too late for him: on November 11, 1947, he was taken to the hospital directly from his laboratory, and died a few days later, on November 19. His burial in the Cluj Central Cemetery was a national mourning day organized in his honor by the University that he had supported faithfully and generously.

The current text is based on the original written by Gheorghe Racoviţă (1940-2015, the grandson of the scientist). Translated by Calin Cascaval and Oana Marcu (great-grandchildren of the scientist).